Sea trout (called sewin in Wales, white trout in Ireland) and brown trout are the same species (Salmo trutta). A combination of genetics and environmental factors (principally lack of food) will mean that some trout will go to sea to feed before returning to spawn. This is called an ‘anadromous’ lifestyle.

Trout also migrate within the river and from lake to river. What prompts some trout to migrate? Research by Professor Andy Ferguson helps explain. Click here for the summary and here for the full paper from the Journal of Fish Biology 2019.

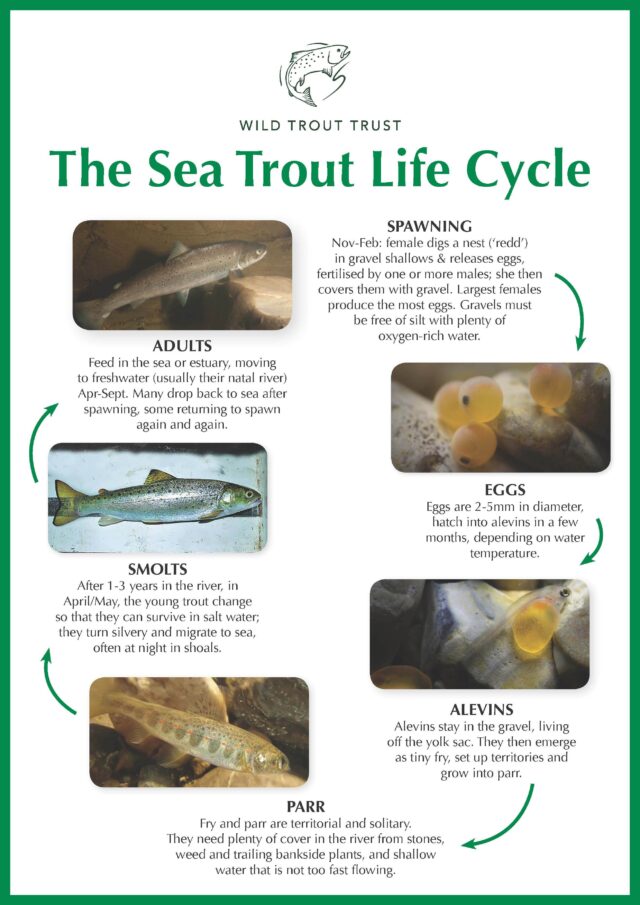

Sea Trout Lifecycle

The sea trout lifecycle diagram is available as a PDF in English and in Welsh. These are clearer to read than the image above, and can be downloaded and printed if required (A4 size).

Young trout of 1 to 3 years old and 5 to 7 inches long will go through some physiological changes which includes the ability to cope with salt water and changing to a silver colour These small silver trout are called smolts. Smolts will shoal together to migrate to sea, usually around late March/April and usually at night.

Going to sea gives the trout access to a much richer source of food, so sea trout will often be substantially bigger than the resident brown trout of the same river. Specimens of 10kg have been caught in the rivers of Wales and Scotland. The River Ouse in Sussex is known to produce the largest averaged size of sea trout of any river in England and Wales (based on EA Angler Catch Return data).

In many rivers, the majority of sea trout are female, and their larger size means that they produce more eggs – a more valuable source of future generations than milt, as only a small volume of milt is required for fertilisation. An average of 800 eggs are produced per pound weight of hen fish, although this figure can vary considerably. Egg size can also vary but in general larger, older sea trout will produce more and larger eggs, and hence these are the most valuable fish to return — and not take home to eat!

Large male sea trout will develop a prominent ‘kype’ or hooked lower jaw as they prepare for spawning.

Sea trout will return to their natal river to spawn, and can start coming back to the river after only a few months at sea. Small sea trout are variously called finnock, peal, herling and whitling (although whitling is a term generally used for small sea trout in estuaries).

Sea trout can enter the river at any time from April onwards, but most will arrive in the summer and early autumn (June to October) and wait in deep pools or in areas of the river with good overhead tree cover until it is time to spawn. They are hard to see during the day and will tend to move at night. Often the only clue that sea trout are in the river at all is a large ‘splosh’ as they jump.

The video below shows a shoal of sea trout circling around a pool (and a chub swimming close to the camera — black tail, no spots, large golden scales at 36 seconds). This shoaling and circling behaviour may be because they are waiting below a barrier for a lift in water levels before they move upstream.

The video is by Jack Perks, who is a passionate and expert fishy film maker!

Salmon and sea trout

Unlike most salmon, sea trout do not usually die after spawning. Around 75% of sea trout will return to the sea to feed and then come back again to the river to spawn.

Like salmon, sea trout do not generally feed in fresh water, even though they may enter fresh water many months before spawning.

Click here for a guide to sea trout recognition, produced by the Atlantic Salmon Trust.

There are some subtle differences between the appearances salmon and sea trout. The ‘fish cam’ video below illustrates them perfectly:

Sea trout or brown trout?

Telling a sea trout from a brown trout in the river can be difficult once sea trout lose their distinctive silvery colouration. This article from the WTT Autumn 2019 newsletter gives some suggestions on how to tell the difference.

When they first enter the river, sea trout are very silver in colour. Once in the river for a while, they lose this silver colour and look like resident brown trout, only bigger! The only sure way to tell if a trout has been to sea is to take a scale and ‘read’ it under magnification – the growth rings will show if it has grown quickly on the rich food in the sea.

Sea trout and salmon can suffer considerable stress pre- and particularly post- spawning, so it not unusual to see sea trout with white or reddish fungal growths in the early winter. As long as these infections are not too extensive, these fish will return to sea and recover to spawn again.