A spotlight on our own iconic, native trout species in the British Isles.

Introducing the brown trout — from basic identification, through to feeding habits, geographic spread, fishing traditions and more. We explain why we love having it as our totem species – and how a whole, pragmatic approach to freshwater conservation has been built around these beautiful fish.

Maybe we’ll be also able to show why this fish holds a lifelong fascination for anglers, biologists and nature-lovers alike – even becoming officially the UK’s favourite fish species in 2016.

Brown Trout basic biology

Classification

Species name: Salmo trutta (Linnaeus 1758)

Family: Salmonidae

Order: Salmoniformes

Class: Teleosti

Phylum: Chordata

Kingdom: Animalia

Click here for a diagram of the lifecycle of the brown trout.

Arriving at the above clean and neat official verdict has not been an easy ride! There are reported to have been over 50 different species previously named within what is currently considered the single “Brown Trout/Salmo trutta” species (or species complex if we get fancy). Also, before going any further – Yes, sea trout in the UK and “resident” brown trout are both “Salmo trutta”.

Even today there are passionate arguments using combinations of genetic (inherited) and phenotypic (outward) characteristics for considering certain “Salmo” trout as a truly separate species. One good example of that is the ferox trout which has gone back and forth on whether true ferox trout are captured under Salmo trutta or some variation on a designation like “Salmo ferox” for years.

There is a big difference between the fish proposed to be a true ferox versus any large trout that eats other fish. All trout will eat other fish when they get the chance – and some grow very large partly as a result of that. But there are specific breeding and feeding habits as well as specific genetic characteristics that are unique to ferox.

Nowadays, there is even a move back towards a much-expanded species listing for our “salmo-trout” species complex. Trout genetics expert Professor Andrew Ferguson feels there are currently over 40 species captured under the “Salmo trout” umbrella.

He argues that we happily recognise loads of diversified cichlid fish species (as well as other non-fishy groups e.g. “ichneumonid” wasp species). That could make it difficult to argue that such an adaptable animal as a trout has not radiated into multiple species.

Professor Ferguson also argues that lots of conservation designation focuses on the species (or sub-species). That is highly significant since there is a clear benefit to the conservation of “trout” when recognising and protecting species richness and uniqueness is formally adopted.

A major factor in creating all those “nominations” for separate species comes from their freakish adaptability.

The Amazing Variety of Brown Trout

To start with, it has one of the highest degrees of genetic variation of any (known) vertebrate – but not only that, brown trout show the capacity for that to translate into huge physical variation too. Using body size as an example, the weight of most vertebrates varies between individuals by about 15% (measured statistically as a coefficient of variation, at a given age, in a single population). When you look at Salmo trutta that variation figure is around 60% and you can read more about this here

Jonny’s “Spot the Difference” project

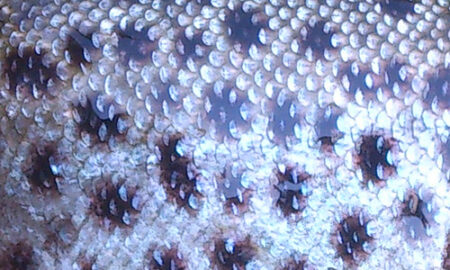

It doesn’t stop with just body-size of course and Prof. Jonny Grey of the WTT came up with a great way to find out about and show the surprising and beautiful variation in trout colouration.

By gathering photographs that you — and anyone from around the UK and the World – can submit via email or social media, Jonny hopes to plot a map of the stunning variation of trout spotting patterns.

This underwater video shows trout with a lovely pattern of white halo-ed black and red spots. Typically trout from the same stretch of river will have very similar spotting patterns, as this video shows.

Video courtesy of Chris Conway and the Ness District Salmon Fisheries Board.

Adaptive Variations in Brown Trout Breeding Populations

Lough Melvin is quite famous in fly fishing circles for having these very distinctly separate “types” of trout (Sonaghan, gillaroo, Ferox) maintained as distinct breeding populations.

Those varieties of Melvin brown trout in part maintain their distinct characteristics by using different breeding sites as well as adopting slightly different feeding behaviour. These distinct varieties have been recognised for over two centuries and Professor Andrew Ferguson describes this (and other aspects of brown trout variation) in this presentation recorded at a Wild Trout Trust Annual Get Together.

The gillaroo trout have dazzling red spots and tend to feed around shallower rocky areas. Sonaghan are dark in colour overall – especially the fins – and tend to be found out over deeper, open water. The ferox delays the point at which they mature to be able to reproduce – which allows then to concentrate on switching as quickly as possible onto eating char and other sizeable fish. As soon as their mouths are big enough to engulf an adult char, that creates a distinct “turbo boost” to their growth curve and they can then rapidly achieve huge sizes.

Don’t be fooled into thinking that this separation by behaviour and appearance is unique to Lough Melvin though. A really fascinating (and entirely comparable) case has been uncovered for Loch Laidon brown trout sub-species/strains/distinct breeding populations. That example includes a form of trout with pale flanks and large eyes that feeds on prey on the lake-bed at huge depths – something never recorded before.

Adapted to Marine & Freshwater Life

Whatever way you slice it, these creatures are extremely adaptable and pull of some remarkable biological tricks — like changing from freshwater to saltwater life! ANY individual brown trout is physically capable of undergoing the physiological transformation needed to migrate out to sea from a river. Many resident brown trout populations are likely to have been founded by sea trout questing up into new freshwater habitats and breeding.

Limits to Adaptation

Trout, as adaptable as they are, still have basic sensitivities that make them indicators of problems and positives in our rivers. They cannot tolerate low oxygenation to anything like the same degree that many other species of fish can.

They also need to have access to multiple distinct types of habitat that suit each of the three key stages of their lifecycle (spawning, juvenile and adult). That means two things:

- The habitat must exist (structural quality and variety)

- The habitat must be accessible (connectivity of essential habitat patches)

Both of those things are predictors of wider ecosystem health too.

Finally, somewhat linked to their intolerance for low oxygen, they also need cool water – which implies a need for patchy shading and healthy riverside plant and tree growth (also great predictors of ecosystem health).

Brown Trout Fly Fishing

There have been many beautiful books and many significant lifetimes dedicated to the pursuit of catching trout – particularly using artificial flies. The automatic insertion into the whole food web that a fly fisher takes on in order to imitate the prey of the wild trout creates a powerful connection.

Famous wines take on the characteristics of the geology and climate of where their grapes grow. In the same way, river valleys and lake systems colour the characteristic plant, insect, fish and complete wildlife ecosystem that they support.

The addictive pursuit of plugging in to all those recognisable “personalities” of different trout waters is, in no small part, responsible for the original formation of the Wild Trout Society. Set up by a passionate group of anglers, over time the transformation to registered charity caused the name change to the Wild Trout Trust.

Our backstory goes a long way to explaining why we view our wild brown trout as icons of wider river ecosystem health.

Not many people capture the (sometimes eccentric or maybe quietly obsessive) character of an incurable passion for catching wild trout on a fly as well as Rolf Nylinder…

Catch and release fishing, as well as habitat protection, are hugely important strategies to ensure the continued existence of wild, self-sustaining populations of brown trout. With increasing pressures on the natural world, it is important to recognise how we need to adapt our practices and attitudes to keep pace with the times.

A prime example of that can be found in the deep tradition of trout fishing on Ireland’s Lough Corrib – a 44,000-acre natural limestone lake for centuries harvested for its trout. The tactics and practices of fishing on the lake are strongly embedded in the local community and are an important shaping force in the culture of the area.

Over time, it has also become a highly significant lure for travelling anglers which supports many strands of that local economy too. With increases in population as well as tourist angling pressure and the advent of outboard engines (and increased pressures on the spawning tributaries that are the engines of lakes like Corrib) the assumption that the trout would never run out comes into question.

One of Corrib’s most successful fly anglers, Basil Shields, realised what hung in the balance if anglers were not to alter their assumptions and begin to return trout – rather than assuming they should take it to eat or to sell on.

There are now growing numbers of anglers (and associated social media groups) taking serious and considered decisions on how best to protect both the species and their valuable sport for the future.

Brown Trout Distribution

The truly native range of Salmo trutta is from Iceland/the Barents Sea in the north, the Atlas Mountains of North Africa in the south and stretching eastwards (from that westerly limit of Iceland) as far as the Caspian and Aral seas in Kazakhstan. That spread has been determined by the survival within ice-free refuge areas and then subsequent colonisation following the end of the last ice age.

Those colonisations (and re-colonisations following disturbance) are not limited to rural areas and with the trend of improving health in our urban rivers, wild trout are becoming an increasingly common sight in the post-industrial rivers and streams of our towns and cities. That is a powerful symbol for an optimistic future – and also places a responsibility to avoid allowing conditions to slip back. The Trout in the Town projectseeks to contribute to protection and improvement efforts for our urban brown trout – and grayling — populations.

However, the fondness of (particularly) the British for taking reminders of home with them around the world has led to brown trout being introduced far beyond their original native range. North and South America, Australia and New Zealand, even the high mountains of Bhutan and many more places (including Japan) have seen the species introduced in a pretty reckless fashion.

The omnivorous habit and natural adaptability makes introductions to ecosystems that have never experienced a historic “arms race” of co-evolution incredibly unpredictable in terms of potential damage. With the subsequent social and economic value developing from many of those introductions, it is now an incredibly complicated picture.

Brown Trout Spotlight: Take Home Messages

The native trout of the British Isles has a passionate following of scientists, wildlife-lovers, anglers and even enjoys a place of strong affection with the general public who may never get to see one up close. Strong traditions of culture and art surround them and the extremely wide variation in terms of their genetic material and outward characteristics are precious elements of our heritage.

Brown trout also act as scientifically-relevant indicators of ecosystem health – spanning flowing water, land-locked stillwater systems and even the marine environment. Working to conserve wild, self-sustaining populations of trout is a good way to have positive impacts on aquatic AND terrestrial habitats – since there are complex and powerful links between waterways and their surrounding catchment.

You can join the fight to protect the habitats and ecosystems that support wild brown trout by becoming a member today – with our thanks and great appreciation.