Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are not native to the UK – our only native trout is the brown trout (Salmo trutta). The native range of rainbow trout borders the northern Pacific ocean from America to Russia but they have been introduced to many countries, including the UK. They are also very widely farmed both as a table fish and to stock lakes and some rivers as a sport fish.

Both brown and rainbow trout have the ability migrate to sea, returning to spawn in freshwater. Rainbow trout that spend part of their lives at sea are called steelhead, brown trout that go to sea are called sea trout (or sewin or peel or many other local names). But for both species, there are lots of life history strategies that see them moving around within rivers, between rivers and lakes and between freshwater, brackish and salt water.

Relationship between brown and rainbow trout (taxonomy)

The genus Oncorhynchus includes rainbow trout, cutthroat trout and Pacific salmon and is a relatively recent classification. Prior to 1989, rainbow trout were included in the Salmo genus due their similarity to brown trout in terms of lifecycle, habitat, food sources and appearance but studies of the form and structure (morphology) and genetics determined that the salmon and trout of the Pacific basin were a distinct genus and given the name Oncorhynchus.

The genus Salmo now refers only to Atlantic salmon (S. salar) and trout (S. trutta) and its related sub-species, which are native to Europe and North Africa.

There is another group of ‘trout’, which are not actually trout but are biologically charr – members of the genus Salvelinus. These include brook trout (S. fontinalis), lake trout (S. namaycush), bull trout (S. confluentus) and Dolly Varden (S. malma). All of these are native to North America. The other family member – Arctic charr (S. alpinus) is widespread in the northern-most areas of the northern hemisphere and includes populations in the deep glacial lakes of Scotland, Wales and north west England.

Oncorhynchus, Salvelinus and Salmo are genera within the family Salmonidae. They are native only to the northern hemisphere but many species (especially the rainbow and brown trout) have been introduced to the southern hemisphere and have established self-sustaining populations there, most notably in New Zealand and South America.

Rainbow trout and brown trout can be interbred in a fish farm environment, resulting in ‘brownbows’, but their different spawning times and genetic differences mean that this interbreeding is very unlikely to happen in the wild. In the UK, some fish farms sell Arctic and brook charr, their hybrid (the ‘sparctic’) and hybrids of brown trout and brook charr (the ‘tiger’ trout), See, for example, Torre Trout Farms.

Appearance

Rainbow trout are so called because they may have a very distinct red or pink lateral line. They are often called ‘redband trout’, although strictly speaking this description relates to rainbow trout from the Columbia, MacLeod or Great basins of the western USA.

The colours of the spots can help distinguish the trout of different genera:

Oncorhynchus only have black spots (rainbow trout — left).

Salmo have black, red and orange spots (brown trout — centre).

Salvelinus can have white, yellow, red, orange and lilac spots (brook trout — right).

Rainbow trout and cutthroat trout are closely related and often look very similar. Cutthroat trout have a red, orange or pink line that runs along their lower jaw. Rainbows and cutthroats share very similar habitat requirements and they spawn at around the same time, so interbreeding is common. Because rainbow trout have been introduced so widely and are so successful, they are endangering unique strains of cutthroat trout in their native rivers of the western USA and Canada.

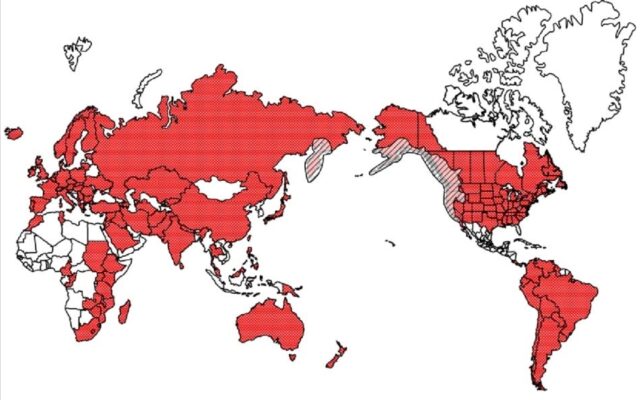

Native and introduced range of rainbow trout

The rainbow trout is native to the rivers and lakes draining into the Pacific on the west coast of North America. Their range extends from Mexico in the south to Alaska in the north. Rainbow trout are also found on the Kamchatka Peninsula on the Pacific coast of Russia (not far from Alaska).

Rainbow trout have been farmed and introduced to rivers and lakes outside their native range since the 1880’s, most famously farmed at the McLeod River and San Leandro hatcheries in California. These two hatcheries are the original source of most of the artificially bred rainbow trout across the world.

Rainbow trout were initially introduced and then farmed across the United States – a practice that continues to this day. Many rivers and lakes in the USA and Canada were (and still are) stocked with rainbow trout to attract angling tourists.

In the USA, glacial lakes in the Sierra Nevada in California were originally stocked with rainbow trout by hiking up the mountains with buckets of trout. When planes and helicopters became available, the lakes could be stocked with more fish and a lot less effort. The ‘carpet bombing’ of lakes with rainbow trout was (and still is) carried out each spring to replenish the population that was thought to have died over the winter when lakes were frozen. Subsequent research showed that 70% of the stocked lakes had developed self-sustaining populations.

The video below shows the stocking of Alpine lakes in Wyoming by helicopter.

Widespread stocking has consequences on the native wildlife. The lakes of the Sierra Nevada in California had no native fish, but they did have thriving populations of mountain yellow-legged frog. The introduced rainbow trout led to a huge reduction in the frog population. Since 2001 the stocking of most of the lakes in the Sierra Nevada has ceased and efforts have been made to remove the rainbow trout from some lakes to allow the natural ecology to recover.

Rainbows were also introduced in many other countries where they often established wild, self-sustaining populations. Rainbow trout are now present on every continent except Antarctica.

For more information on how rainbow trout became so widespread, read Anders Halverson’s excellent book ‘An Entirely Synthetic Fish – How Rainbow trout Beguiled America and Overran the World’.

The establishment of rainbow trout beyond its natural range has often been positive for angling and tourism, particularly in New Zealand and South America. In these areas, brown/sea trout have also been successfully introduced, but the populations of native fish and other native wildlife have frequently suffered or been extirpated by the invaders. For example the New Zealand grayling (Prototroctes oxyrhynchus), became extinct in the 1930’s due, at least in part, to competition and disease from introduced trout.

Balkan rivers such as the Soca in Slovenia contain marble trout, which are an endemic sub-species of brown trout, Salmo trutta marmoratus. In order to retain the unique characteristics of these fish and prevent interbreeding with brown trout, these rivers have been stocked with rainbow trout which are now successfully breeding in many places.

Below: The River Idrijca, a tributary of the Soca, Slovenia, and a ‘wild’ rainbow trout. Photos by Charles Carr and Kris Kent.

Rainbow trout have proved to be immensely successful interlopers, not always welcomed by everyone!

The video below shows the impact of stopping stocking in Montana, one of (if not) the most popular trout fishing destinations in the USA.

Rainbow trout biology

Rainbow trout are very similar to brown trout in terms of their feeding habits, taking mostly invertebrates on or below the surface of the river or lake. Their primary diet of river flies is supplemented by terrestrial insects or other fish.

Their lifecycle is also very similar except that, in the wild, rainbows will spawn in the spring, whereas brown trout spawn in the late autumn or winter. Spawning times can be quite variable and are dependent on water temperature — they can spawn as early as January in warm areas such as California or as late as June in colder areas. They generally spawn as water temperatures are rising.

Both rainbow and brown trout can have a sea-going (anadromous) form: sea trout are brown trout that have spent some of their life at sea, steelhead are rainbow trout that have gone to sea. Where such a strategy is adopted, the young fish (parr) live in freshwater, and then smoltify and go to sea at around 2 years of age. Having spent some time (often years) at sea, steelhead return in two distinct phases, either the summer run (May to October) or winter run (November to April). Both sea trout and steelhead can be ‘repeat spawners’ – they will spawn, return to sea and come back to spawn again, unlike Atlantic and Pacific salmon which are more likely to die after spawning.

Steelhead populations have undergone a major decline in spite of attempts to produce huge numbers of baby steelhead in hatcheries to mitigate for the effect of the large dams which prevent both steelhead and Pacific salmon from reaching their spawning grounds. Anglers and fisheries biologists are increasingly of the view that the hatcheries have undermined the ‘fitness’ of both wild salmon and steelhead to survive in the wild and, where dams have been removed, prevented wild fish from naturally re-colonising.

Artifishal is a disturbing film about people, rivers and the fight for the future of wild fish (Pacific salmon and steelhead) and the environment that supports them on the Pacific coast of America.

Habitat requirements for brown and rainbow trout are broadly similar – both need clean, well oxygenated water, a good supply of food in the form of invertebrates and complex habitat such as tree roots, woody material, rocks and boulders to provide cover from predators. Rainbow trout are more inclined to shoal (live in groups) than brown trout. They are also more tolerant of higher water temperatures.

Rainbow trout in the UK

Rainbow trout are very commonly stocked into lakes and reservoirs to provide angling opportunities. Rainbows have a reputation for being exciting fish to catch and can grow to very large sizes. Their tolerance of higher water temperatures can make them a little easier to keep in small lakes through warm summers than brown trout. Find out more about stocked trout fishing here.

In the UK, all the rainbow trout that are farmed for either the table or for stocking are infertile (triploid) or all-female. A number of colour variants exist (e.g. ‘golden’, ‘blue’) but they are the same species as ‘normal’ rainbows.

Unlike most other countries, where self-sustaining populations from introduced trout have become established in many rivers, the only UK self-sustaining populations is in the Derbyshire Wye. Hatchery rainbows were shipped from the USA to the UK as early as 1884 – 5 and are first recorded on around 1907 – 1910. According to American fish biologist Robert Behnke ‘the 1885 shipment to the U.K. would have been highly diverse in ancestry with high heterozygosity for natural and artificial selection to effect rapid adaptive change’. The rainbows in the River Wye certainly did adapt well and now make up around 25% of the fish caught on the Derbyshire Wye, co-existing alongside the indigenous wild brown trout population.

Historically, there have been reports of other rivers with populations of rainbow trout, including the Rivers Chess, Misbourne and Lambourn but these do not appear to have self-sustaining populations today. Rainbow trout parr occasionally turn up in rivers with stocked rainbows or near fish farms and rainbow trout are occasionally seen attempting to spawn. This is possibly because the process for creating purely female triploids for stocking, which has been in place since around the mid-1980’s, is not fool-proof.

The video below, shot by Jack Perks, shows rainbow trout in Derbyshire.